While the name Sylvia Beach may not be familiar to you, you have probably heard of two of her greatest accomplishments: she owned and operated the Shakespeare and Company bookstore in Paris and she published James Joyce’s Ulysses in 1922.

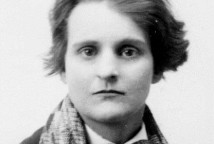

Born in 1887, Sylvia enjoyed a comfortable, middle-class New Jersey upbringing. She lived in France with her family for two years while her father, a Presbyterian minister, worked for the American church in Paris. Sylvia traveled to Europe again to learn Italian, Spanish and French. The shortage of manpower during World War I created opportunities for young women like Sylvia, who volunteered as an agricultural worker in the French countryside and for the American Red Cross in Belgrade. While she enjoyed the physicality of the work, the rampant chauvinism and patriarchal inequalities of the time were disappointing to her. Witnessing the ravages of war first hand, Sylvia was determined to contribute meaningfully to the world.

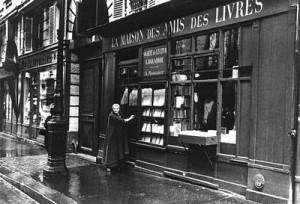

Sylvia’s lifelong mission came into focus when she met fellow book lover Adrienne Monnier, who owned and operated her bookshop La Maison des Amis des Livres in Paris. Adrienne’s occupation was unusual for a woman at the turn of the 20th century. She invented the concept of the lending library in France mostly to benefit women, few of whom had the budget to buy their own books. Adrienne advanced the field of bookselling beyond mere commerce, incorporating an intellectual and artistic dimension. This inspired Sylvia to open her own English language bookshop in 1919 — thanks to a loan from her mother and help from Adrienne.

Sylvia’s lifelong mission came into focus when she met fellow book lover Adrienne Monnier, who owned and operated her bookshop La Maison des Amis des Livres in Paris. Adrienne’s occupation was unusual for a woman at the turn of the 20th century. She invented the concept of the lending library in France mostly to benefit women, few of whom had the budget to buy their own books. Adrienne advanced the field of bookselling beyond mere commerce, incorporating an intellectual and artistic dimension. This inspired Sylvia to open her own English language bookshop in 1919 — thanks to a loan from her mother and help from Adrienne.

Shakespeare and Company was first located at 8 rue Dupuytren. Two years later, Sylvia moved the bookstore to 12 Rue de l’Odéon, across the street from Adrienne’s bookstore at 7 Rue de l’Odéon. Sylvia and Adrienne developed a lifelong friendship, became lovers and lived together until Adrienne’s death in 1955.

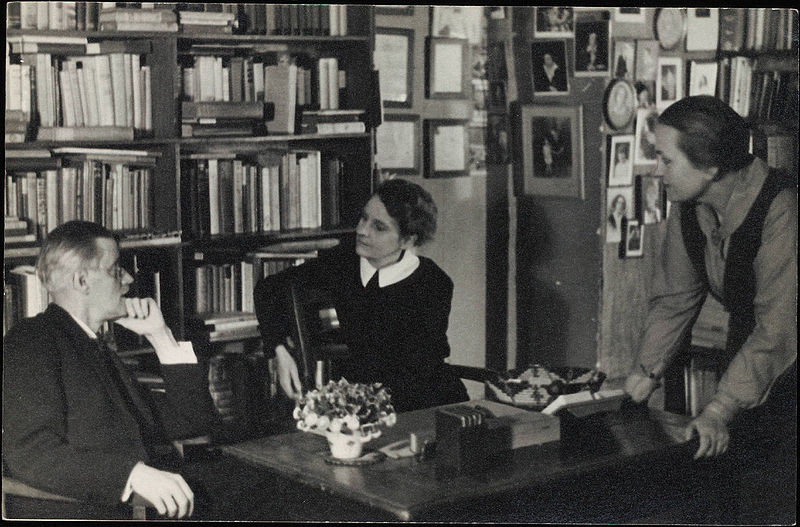

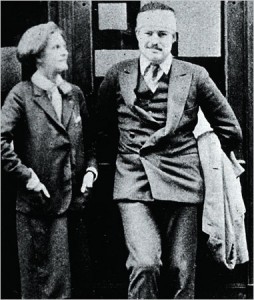

Modeled after Adrienne’s concept, Sylvia’s bookstore was a lending library first and foremost. Her mission was to create both a book store and a haven where book lovers could gather to read. In her memoir Shakespeare and Company, Sylvia writes that Ernest Hemingway called himself her best customer. Sylvia agreed with Ernest and added that it would not have mattered to her whether he was a paying customer or not; they had a great friendship because they genuinely liked each other. About Sylvia, Ernest said: “No one that I ever knew was nicer to me.”

Modeled after Adrienne’s concept, Sylvia’s bookstore was a lending library first and foremost. Her mission was to create both a book store and a haven where book lovers could gather to read. In her memoir Shakespeare and Company, Sylvia writes that Ernest Hemingway called himself her best customer. Sylvia agreed with Ernest and added that it would not have mattered to her whether he was a paying customer or not; they had a great friendship because they genuinely liked each other. About Sylvia, Ernest said: “No one that I ever knew was nicer to me.”

According to a review in The Guardian, The Letters of Sylvia Beach, edited by Keri Walsh, reveal a treasure trove of information about her life:

While it is easy to imagine keeping a bookshop/library where Hemingway, Gide and Maurois constantly pop in for a chat and a biscuit to be some kind of ideal, unalienated labour, Beach’s letters show that it was far more tricky than that. For every witty exchange with a literary tyro there is an annoying “bunny” (the term Beach used to describe her abonnés or subscribers) who needs soothing and settling and making a fuss of. The upstairs neighbours constantly flood her premises, one of her sisters in the US is acting weird and, strange to say, some of her literary discoveries won’t play nicely together.

Sylvia nurtured many writers, some to a fault. One of her most famous protégés was James Joyce. She took on the enormous challenge of getting his controversial Ulysses published. The book had been judged as too obscene to be published. Despite the controversy, Sylvia believed in James’s talent and worked tirelessly on his behalf. He did not reciprocate her loyalty and took advantage of her emotional and financial generosity. The introduction of Janet Flanner’s Paris Was Yesterday mentions Sylvia’s disenchantment with James:

Ulysses was the paying investment of his lifetime after years of penury,

Sylvia said, while hardly acknowledging the fact that the publishing costs almost wiped out her Shakespeare and Company. The peak of his prosperity came in 1932 with the news of his sale of the book to Random House in New York for a forty-five-thousand-dollar advance, which, she confessed, he failed to announce to her and of which, as was later known, he never even offered her a penny:

I understood from the first that, working with or for Mr. Joyce, the pleasure was mine—an infinite pleasure: the profits were for him.

After the fall of Paris in 1940, Shakespeare and Company stayed open but a confrontation with a Nazi officer in 1941 forced Sylvia to close the bookshop. The officer had seen a copy of Finnegans Wake in the bookshop’s window and wanted to buy it, but Sylvia refused. As he left, the officer threatened to come back with reinforcements to confiscate the bookstore’s holdings. Four hours later, Sylvia and several friends had moved all the books out of the shop, painted over the store front and closed down the shop. Sadly, the bookstore never reopened in its original location, but in the 1960s a fellow bookstore owner, George Whitman, renamed his shop in Sylvia’s honor.

George opened Le Mistral at 37 Rue de la Bûcherie in 1951. After Sylvia’s death in 1962, George renamed his shop Shakespeare and Company as a tribute to her. As an interesting side note, the bookshop makes a cameo appearance in the recent movie Midnight in Paris.

Today, the spirit of Sylvia’s bookshop lives on in its modern incarnation near Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris. George’s daughter Sylvia Whitman continues her father’s and namesake’s tradition of providing a warm and welcoming atmosphere in her bookshop, with living arrangements and more than a dozen beds for young writers-in-residence.

Further reading and viewing

Shakespeare & Company, by Sylvia Beach

Sylvia Beach and the Lost Generation, by Noel Riley Fitch

The Letters of Sylvia Beach, edited by Keri Walsh

Paris Was Yesterday, by Janet (Genêt) Flanner

Review of Keri Walsh’s The Letters of Sylvia Beach, The Guardian

Books And Their Makers: Sylvia Beach And James Joyce, The New Yorker

Ex-Pat Paris as It Sizzled for One Literary Lioness, The New York Times

Paris Was A Woman, Zeitgeist Films

Sylvia Beach Interview, excerpt from Paris Was A Woman, Zeitgeist Films

Today’s Shakespeare and Company bookstore

Shakespeare and Company, Part 2, Sylvia Whitman (George Whitman’s daughter)

George Whitman, Paris Bookseller and Cultural Beacon, Is Dead at 98, The New York Times

Midnight in Paris, a Historical View, The New York Times

Originally published on the New York Women in Communications blog Aloud.

Categories: Culture, Women's History Month