If you haven’t heard of author and fashion designer Elizabeth Hawes, it’s probably because she was blacklisted for her allegedly “Communist” work with American labor unions. J. Edgar Hoover opened up an FBI file on Hawes in 1940, years earlier than the thousands of other files that were opened during the Cold War. Although her file was closed in 1947, Hawes suffered professionally and never regained the stature and success she had achieved in the 1930s.

Elizabeth Hawes was a fashion copyist, stylist and assistant designer in Paris in the 1920s, a successful fashion designer with her own business in New York in the 1930s, and a machine operator at an aircraft war plant and union organizer for United Auto Workers in the 1940s. Through it all and beyond, she was a writer, moving from fashion critic for The New Yorker to bestselling author of nine books to columnist for the left-leaning PM newspaper and the Detroit Free Press. She was married twice, to Ralph Jester (1930-1934) and director Joseph Losey (1937-1944) with whom she had a son, Gavrik Losey. Her later years were lived in relative obscurity, as she tried to escape the black cloud of McCarthyism by decamping to St. Croix in the late 1940s. She returned to New York intermittently, trying out California in the 1950s and 1960s. A hard drinker for most of her life, she eventually died of cirrhosis of the liver in 1971 while living at the Hotel Chelsea.

The Early Years

Elizabeth Hawes was born on December 16, 1903 to John Hawes, a mild mannered assistant manager for Southern Pacific Steamship Lines, and Henrietta Houston, an accomplished Vassar graduate and progressive-minded suffragette. Growing up in Ridgewood, NJ with her two sisters and brother, Elizabeth traveled to New York City twice a year with her mother to window shop fashions, visit museums and eat at fine restaurants. Her grandmother bought her a Paris gown every year. Inspired by her Montessori schooling, Elizabeth began sewing clothes and hats for her dolls and for herself at the age of 10. When she was 12, she began sewing clothes for other children. Some of her creations were sold at a dress shop in Pennsylvania.

every year. Inspired by her Montessori schooling, Elizabeth began sewing clothes and hats for her dolls and for herself at the age of 10. When she was 12, she began sewing clothes for other children. Some of her creations were sold at a dress shop in Pennsylvania.

Following in their mother’s footsteps, Elizabeth and her sisters attended Vassar. Elizabeth’s first love was fashion design, but she discovered economics at Vassar and took every course she could on the topic. Her thesis was on Ramsay McDonald, the British leader of the Parliamentary Labour Party. While at Vassar, she debated whether she should pursue her interest in economics and vacillated for some time. Eventually her love of fashion won out, and she set sail for Paris after graduating. The connections she made at Vassar would serve her well when she started her own couture house in New York.

Paris

On arrival in Paris in 1925, Elizabeth began her quest to become a couturiere by copying Paris fashions for an American house. She later remarked: “The desire [to work] was so great I did not for one moment consider the ethics of the matter.” She also wrote witty critiques of the hype surrounding Paris fashion under the nom de plume “Parisite” for The New Yorker. She firmly believed that American women should not have to follow the dictates of the Paris fashion world. She felt American designers were best positioned to design for American women, especially with regard to the emergence of sportswear. She also believed clothes should be comfortable and championed individual style over fashion.

While in Paris, Elizabeth worked as a stylist for Macy’s, then for Lord & Taylor, eventually landing a position as an apprentice for Nicole Groult, the sister of fashion designer Paul Poiret. She wanted to design for French women, but eventually realized the Paris fashion world was all but closed to an aspiring American designer. She decided to move to New York to pursue her ambitions.

New York

Upon her return to the U.S. in 1928, Elizabeth started a fashion house with Vassar classmate Rosemary Harden. Hawes-Harden cultivated a salon atmosphere, serving tea and encouraging conversation. A year  later, Harden decamped, and Hawes decided to continue on her own.

later, Harden decamped, and Hawes decided to continue on her own.

Some of her couture pieces, all irreverently titled, are in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume collection, including her bias-cut silk shantung Alimony dress and Misadventure cape.

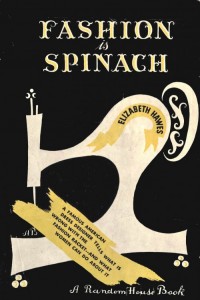

Elizabeth Hawes holds the honor of being the first American designer to hold a fashion show in Paris in 1932. The Parisian press did not cover it. Indeed, Parisian women were not going to buy fashions from an American designer. She wrote about this fiasco in her first book, Fashion is Spinach, published in 1938.

The book was titled after a cartoon by Carl Rose printed ten years earlier in The New Yorker, depicting a mother sitting at the kitchen table telling her daughter “It’s broccoli, dear,” while the child answers, “I say it’s spinach and I say the hell with it.” Elizabeth included an account of her more successful showing of her fashions in Russia in 1935. The book is entertaining, thought provoking and well written, and includes her trademark witty critiques of the fashion industry. While she made a name for herself as a successful fashion designer during the Great Depression, the success of her first book cemented her stature as an author.

“I say it’s spinach and I say the hell with it.” Elizabeth included an account of her more successful showing of her fashions in Russia in 1935. The book is entertaining, thought provoking and well written, and includes her trademark witty critiques of the fashion industry. While she made a name for herself as a successful fashion designer during the Great Depression, the success of her first book cemented her stature as an author.

Elizabeth’s second book, Men Can Take It, reveals her humanist side: she wanted to liberate both women and men from fashion dictates and espoused the unpopular view that people should dress to please themselves. She was in favor of men wearing skirts, also.

With the onset of World War II, Elizabeth decided to close her business in 1940, re-emerging briefly to design a Red Cross uniform. She wrote a column for the radical newspaper PM, whose writers were deemed guilty of being either Communists or sympathizers. Unbeknownst to writers at PM, the FBI opened files on all of them. A decade later, when the official witch hunt began, even PM subscribers were considered suspect.

In the spring of 1943, Elizabeth decided to support the war effort by taking a job as machine operator at Wright Aeronautical in Paterson, NJ. Her experience there led her to write Why Women Cry, or Wenches with Wrenches, published later that year. Despite the completely different subject matter, the book quickly became a success, following the path of her previous books about fashion.

Detroit and the UAW

By 1944, Elizabeth’s marriage to Losey had disintegrated, and she moved to Detroit to take a position as a union organizer for the UAW. While in Detroit, she became a columnist for the Detroit Free Press. Her first column made a plea for a reduced, 30-hour workweek and daycare. Her column generated so many letters that the newspaper had to create a second column to publish the letters and Elizabeth’s responses.

By 1944, Elizabeth’s marriage to Losey had disintegrated, and she moved to Detroit to take a position as a union organizer for the UAW. While in Detroit, she became a columnist for the Detroit Free Press. Her first column made a plea for a reduced, 30-hour workweek and daycare. Her column generated so many letters that the newspaper had to create a second column to publish the letters and Elizabeth’s responses.

In her next book, Hurry Up Please It’s Time, she wrote about red-baiting techniques such as those employed by the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) and how they undermined efforts to organize unions. The book’s title was taken from T.S. Eliot’s The Wasteland, to provide a distinctly downbeat and sober tone. This book managed to simultaneously anger both the left- and right-wings by not going far enough in either direction and criticizing both sides.

During Elizabeth’s tenure at the UAW women faced many struggles, but the most significant one was the fact that they were being paid unskilled wages to perform skilled work. This struggle continued for many years in other parts of the world, including Britain, as explored in the entertaining 2010 film Made in Dagenham.

It’s not clear why Elizabeth left the UAW, but there is a good chance she was once again disillusioned after witnessing the chasm between her idealized vision of unions and what it was like to work for one.

Bohemian and Later Years

After leaving Detroit in 1946, Elizabeth returned to New York long enough to secure a contract for her next book, Anything but Love, which covered the media’s influence on women. The tone in this book has been described as biting and darkly satirical, probably the most bitter of all her books. Wanting to escape the conventions of modern society, she wrote in St. Croix, where she became enamored with Bohemian ideals like those of Jack Kerouac and the Beat generation. She completely changed her lifestyle, occasionally returning to New York, but living mostly in St. Croix until 1951. In 1948 she was in New York for a showing of Hawes fashion, old and new. Guests at the show participated in a contest to see who could differentiate between the replicas of 1930s Hawes fashions and her new designs. Not many people could pick out the differences.

Elizabeth’s next book, But Say It Politely, chronicles her experience living in St. Croix, observing first hand its rampant racism. Her final book, It’s Still Spinach, is not a rehash of her first book; it’s a courageous exploration of how and why we adorn ourselves. Elizabeth was most interested in liberating women and men to be creative and comfortable.

Upon her final return to the U.S., Elizabeth enjoyed one final moment in the limelight with the Fashion Institute of Technology’s 1967 retrospective titled: Two Modern Artists of Dress: Elizabeth Hawes and Rudi Gernreich. In California she had befriended fellow fashion designer Gernreich, who famously designed 1964’s scandalous topless monokini.

Sadly, Elizabeth was not in good health when she moved to Hotel Chelsea in 1967, and she succumbed to alcoholism in 1971.

Chelsea in 1967, and she succumbed to alcoholism in 1971.

Though she lived her later years in relative obscurity, Elizabeth Hawes is well known among those who have studied fashion. As Ali Basye writes, fashion bloggers take notice when a Hawes design occasionally becomes available on e-Bay.

The Brooklyn Museum hosted a retrospective of Elizabeth Hawes designs in 1985, and several of her sketches are included in their Fashion and Costume Sketch Collection. The Metropolitan Museum of Art acquired the Brooklyn Museum’s costume collection and hosted a 2010 exhibition on American fashion, including Elizabeth and several other prominent designers.

Elizabeth was interested in mass-marketed clothing for everyone. Her avant-garde tendencies extended to her belief that consumers should be able to tell dress designers and manufacturers what they want and prefer, rather than being spoon-fed whatever materials and fashion happened to be trending. Had social media been available in her day, she might have been an ardent proponent and witty, enthusiastic supporter. I can imagine her Twitter feed as irreverent, provocative and entertaining with pithy sayings like: “A dress should last you three years, otherwise it’s a waste of money,” a comment she was fond of making — much to the consternation of the fashion industry.

Further reading

Most of this blog post was sourced from Bettina Berch’s excellent biography: Radical by Design: The Life and Styles of Elizabeth Hawes, New York, 1988.

Below is a list of the books Elizabeth Hawes wrote. All are out of print, but some are available at NYU’s Bobst and Tamiment Libraries, the NYPL and as secondhand copies and Kindle editions.

- Fashion is Spinach, New York, 1938

- Men Can Take It, New York, 1939

- Why Is a Dress?, New York, 1942

- Good Grooming, Boston, 1942

- Why Women Cry, or Wenches with Wrenches, New York, 1943

- Hurry Up Please, It’s Time, New York, 1946

- Anything But Love, New York, 1948

- But Say It Politely, Boston, 1954

- It’s Still Spinach, Boston, 1954

Originally published on the New York Women in Communications blog Aloud.

Connect with Giuliana on Google+

Categories: Women's History Month

Tags: #WHM, Elizabeth Hawes, Fashion Critic, Fashion Design, UAW, Women's History Month, Writer

One Comment to Women’s History Month: Elizabeth Hawes